One day, Rohit receives the opportunity of a lifetime; a job offer in India with promises of fulfilling the sense of purpose he’s so desperately sought after in a country that seems to have forgotten him. Or so he thinks.

Rohit took a tentative step out of Indira Gandhi International, ducking as a drone sliced through the air above him, spraying aromatic mist in its wake. He clutched his phone tightly to his chest as if the invitation it held—with its temporary work permit and promises of a new life—would protect him.

Sweat beaded and ran down his legs. The night air was sweltering, thickened by Delhi’s monsoons. Rohit eyed the device buzzing close overhead, and it eyed him back through an array of camera lenses nestled among the marigolds affixed to its underside.

In the crowd, he spotted a thin man in a white button-down shirt and dark slacks, holding a maroon sign: “Rohit Ji (USA).” Below it, in gold foil, was the India World logo, a contour of the country’s border packed with outlines of the Taj Mahal, the symbol for Om, and a cross-legged yogi. The sign’s gilding reminded Rohit of the gift envelopes full of cash his grandparents had given him every birthday since he was five. Rohit raised his hand and forced a smile as he hurried to the man. They’d told him there’d be someone waiting; it still seemed extravagant.

The greeter bent to exchange his sign for a round silver tray with neat piles of rice, vermilion, and Indian sweets—the standard Hindu blessing. With a practiced flourish, the man wet the middle and ring fingers of his right hand, dipped them in the scarlet powder, and leaned forward to dot the center of Rohit’s forehead.

Rohit drew back. “Uh, no thanks,” he mumbled.

Noting the confusion on the man’s face, Rohit added, “I don’t want to get my shirt dirty. Later?”

“Of course, of course!” The man bounced like an excited puppy. Plucking Rohit’s small backpack and sizable rolling suitcase from his grasp, he jogged toward a line of auto-taxis.

“Welcome, sir! Come, come!” the man called behind him. Disoriented and nauseated from the heat, Rohit glanced back at the terminal, then scrambled to catch up.

Three weeks earlier, Rohit dug into a plate of sabzi, daal, and raita in his parents’ neat kitchen in the suburban Palo Alto house where he’d grown up.

“Beta, you’re not serious. Why go so far when you have so much here?” his mother asked.

“Mum, you know why,” Rohit said, using a scrap of roti to mop the last of the gati ki sabzi before folding it into his mouth. He explained as he chewed, “It’s good work. In a few years, I might even be able to apply for citizenship. And until then, I can send money back to you and Papa.”

She grunted, pressed the heel of her right hand to her forehead in disapproval, and called out to her husband, “dekho kesi baat kar ra—” A fit of coughing interrupted her; they all waited while it took its course. When she turned back to Rohit, her eyes were wet and bloodshot, her shoulders slumped. He considered admonishing them for not replacing their air filters on schedule, nor wearing the personal air cleaners he’d bought them, but he knew they’d say the same thing they always did. It was fine. Everyone breathed it. And besides, how could they go out in their personal filters when Dr. Suda, their neighbor of forty-three years, and Ms. Nancy, her mother’s walking buddy, could not afford to do the same?

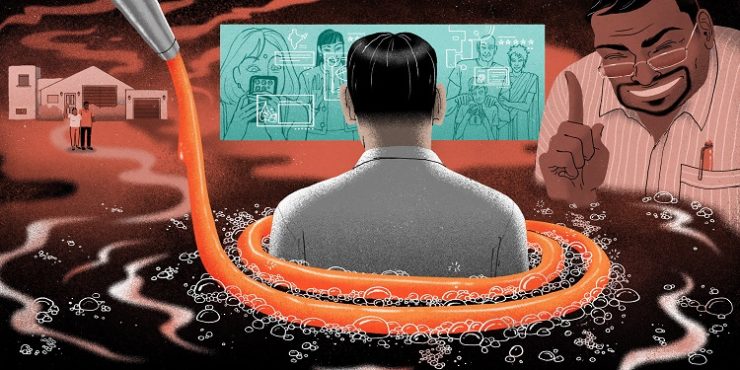

“Your mother is right, beta. This is foolishness. We don’t need money—we are quite comfortable. And we will always help you. We live in the land of opportunity.” His father squinted at him, and Rohit wondered why the man couldn’t see that the brightest had fled across oceans while the rest of his generation camped in their childhood bedrooms, lost in screens. Couldn’t he smell the coal plants burning the air while the last forests were razed for export? Couldn’t he see that the people had divided into two, and decades of tug-of-war had left the country sinking while the modern world rose around it?

Rohit looked up from the smeared remains of his meal. “Papa, there’s nothing here for me. You’ve seen me try. It’s different for you two—you were grandfathered into your jobs. I can live off the dividend, but what life is that?”

“Beta, opportunity does not come looking for you,” his father said, squinting again. “You must create it. There is always a way to make things better.”

Rohit clenched his fists and met his father’s eyes. “No, Papa. Not here.”

Six hours after his arrival in India, Rohit shifted uneasily in a hastily ironed shirt and slacks inside the glass-and-cement command center of India World’s Delhi headquarters. Mr. Mittal, who had introduced himself to the new recruits as their “bossman and friend,” smiled and waved a hand at an open floor plan full of young men and women sitting in swivel chairs a meter apart, gesturing at the air around them. Each figure was ensconced in a translucent cocoon of video feeds from around the theme park. Mittal turned back to his new employees and made a circle with his index finger. “Full three sixty. We see EVERY-THING.”

Rohit nodded and followed as the manager walked them through a gleaming maze of corridors, cube farms, conference rooms, and finally into a theater with a wall of one-way glass. “This exhibit is in its final week of testing, so we’re letting a trickle of visitors find it.” He nodded through the glass at a street in Old Delhi. Old Delhi, in old times. “Many of you will operate stations like this.”

“Is that . . . Chandni Chowk?” Rohit asked, recognizing Delhi’s oldest and busiest market.

Mr. Mittal nodded quickly, his gaze fixed through the window. “Excellent. That Indian History education did some good.”

The Indian government had, for many years, offered scholarships to students of Indian origin in foreign countries who elected to major in Indian Literature or Indian History. Rohit, like many others, had taken advantage.

They watched a jalebi wala, the jalebi wala, at the famous stall known to generations of Delhiites for pumping out the very best of the hot, pretzeled, bright orange sugar treats oozing with syrup. A stick-thin, tanned man wearing a tight turban leaned over a pan of oil. It was as shallow and wide as the round red plastic sleds Rohit had grown up riding down the snowy hills of Lake Tahoe. As he watched, Rohit imagined himself alternating between squeezing the sugary mixture from a pastry bag into the bubbling oil and fishing out cooked sweets from the pan. His brow beaded with sweat, his face hidden in clouds of smoke rising from the oil.

“That can’t be healthy,” Rohit whispered.

“It wasn’t,” Mr. Mittal answered sharply.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to question—”

“The smoke is simulated, the stacks of cooked jalebi cool while targeted with anti-microbial light baths, and we’re working on the nutritional profile.”

“Sounds like you thought of everything. Healthy jalebis . . .” Rohit shook his head in wonder.

“Not completely, but we use a combination of sugarcane and monk fruit as sweetener. And a plant-derived oleophobic prevents the jalebi from absorbing oils. Healthy-er,” Mr. Mittal said, emphasizing the end of the word.

Numbers and graphs projected onto the window measured the man’s material efficiency, output per minute, breaktime usage, guest satisfaction, and estimated revenues. The jalebi wala wiped his brow with the back of his hand, his eyes growing wide as a drop of sweat fell to his pan. When he shot a glance up at the one-way glass, a look of panic on his face, Rohit’s stomach dropped.

Rohit remembered the night he learned why his family didn’t act more Indian. He’d been eight years old, and they’d been walking to their car after dinner at a taqueria in a Palo Alto strip mall when someone yelled after them. A shaggy man in rumpled clothes stumbled out of the darkness, zigzagging toward the three of them, shouting something Rohit couldn’t understand: he told them to go back where they came from. Rohit wondered why he wanted them to go back to the Mexican restaurant.

His mother drew him close and quickened her pace, reaching the car first. His father walked stiffly, avoiding the man’s eyes until his wife and son were safely inside. When the man caught up to his father and grabbed his arm, Rohit heard his father speaking loudly, jovially. He seemed to be smiling, almost friendly with the man. He didn’t sound like his dad—he sounded like a cowboy, a twang rounding the ends of his words. The shaggy man seemed as confused by this transformation as Rohit had been. He hesitated, scratched his head, letting his anger dissolve.

No one spoke on the car ride home. As they pulled into the driveway, his father put the car in park and turned back to Rohit, his thick black eyebrows climbing high on his forehead, the way they did when he had an important lesson for his son. “You saw that man in the parking lot tonight, Rohit. Different is scary, and even a friendly dog will bite if it is afraid. That is why it is not safe to be different here. We must be just like them.” Then his father opened his door and disappeared into the house without another word. Why do we have to be like that man in the parking lot? Rohit wondered. Was that man a cowboy? Was that why his father had used that funny voice?

Years later, when Rohit asked his mother about that night, she’d explained that when his father had grown up, it had been bad to be Indian. If you were in America, you had to act American to be safe. Rohit didn’t understand; how could it be bad to be Indian? Bollywood produced most of the movies, music, and games worldwide. All the superheroes on his shows were Indian. Being Indian meant Diwali (presents!) and Holi, and every kid he knew wanted to celebrate both. But according to Rohit’s mother, his father had grown up despising his brown skin and hating the smell of ginger and garam masala and fried pakoras that filled Rohit’s grandparents’ home. He’d been ashamed of their accents and hid his own. When his parents tried to send him to Hindi summer school, Rohit’s father had threatened to run away from home.

“Should I pretend not to be different, Mum?” he’d asked.

She pinched his cheek lightly and shook it. “You be you,” she said.

Rohit’s grandparents never pretended. They ate different food and dressed in different clothes. They celebrated Diwali and Holi and Navaratri. It was his grandparents who took Rohit to visit India in his early teens. Seeing that colorful, boisterous, inescapably alive place with his own eyes, his pride in his motherland swelled. India had taken its position on the world stage, out-developing and outgrowing America, the country his father idolized.

After college, Rohit had visited the embassy in San Francisco four times to apply for a work visa, but could obtain only a thirty-day tourist permit. He wrote a plea letter to the Indian embassy in New York, reminding them of his Indian blood, his wish to experience his culture, his respect for his heritage. But in the eyes of his mother country, Rohit was not an Indian, but an ABCD. American-Born Confused Desi. For Rohit, the rejections said: India is full.

But then, fifteen years later, he’d gotten a mysterious message promising a chance at a better life. He’d been chosen, based on what, he wasn’t sure. He’d submitted no application, but attached to the message he found a blockchain-verified work permit, a plane ticket, and an India World employee handbook. India, it would seem, needed him after all.

Rohit sweated in his kurta pajama behind a thin metal shelf. Dusty plastic bottles full of spices crowded the narrow surface; a stack of betel leaves fluttered under a polished stone. He carefully arranged thirty paans in neat rows, pointing the tip of each leaf-wrapped spiced breath-freshening triangle upward. He was in the park, on live duty for the first time.

“Ooohh, I’ve heard about these!” said a blonde woman, a sarong around her waist and a cloth bag made of sari scraps over one shoulder. As she spoke, she brought a hand up to her bun to check the flower pinned there. “We should try it. I know they’re supposed to have tobacco, but when in India, right? I mean, shouldn’t we?” She turned to her friend, another blonde wearing a bright green and gold salwar kameez, who nodded hesitantly.

“We have tobacco-free versions, madam,” Rohit offered in carefully accented English, “and our tobacco paans are, of course, nicotine-free.”

“Two tobacco-free, please,” said the first woman. Rohit tapped his payment screen and, within a second, it had scanned the women’s faces, matched their pulse signatures to their entry visas, and debited their accounts. Meanwhile, he clumsily folded two triangular plates from pre-cut newspaper scraps like he’d been trained. The scraps came from copies of The Hindustan Times for August 15, 1986, printed on-site. He placed one paan onto each plate, then held them out to his customers with a slight bow.

“Obsequiousness, five out of ten. Deference, five out of ten. Politeness, five out of ten. Accent, five out of ten. Banter, two out of ten. Bargaining, zero out of ten. Upsells, zero out of ten,” Mr. Mittal rattled off. “A disappointingly below average first month’s performance.”

“Everyone paid the listed price,” Rohit pleaded. “There wasn’t any opportunity to bargain.”

Mr. Mittal stared his employee down. “Rohit, you create opportunities. Opportunities are not simply given.”

As his manager walked away, Rohit burned, feeling the stares of the other new recruits. The ones who had not been disappointingly below average. They were from all over the early-developed world: America, Europe, Australia, Indonesia, Dubai. Anywhere Indians—or those with skin close enough to pass for them—could be found was prime recruiting territory for India World. The one place they didn’t seem to hire from, Rohit had learned, was India itself. Working in a glorified theme park designed to mimic the olden days of the subcontinent no longer appealed to the tastes of the modern Indian.

Rohit felt a hand land lightly on his back. “Follow your instincts on that one,” a man said. Rohit turned to find a middle-aged Indian man, about five foot seven, wearing jeans, a thin wool sweater, and a hairstyle that had been in fashion about ten years earlier. “They’ve started pushing hard on upsells lately,” the man added. “I’m not sure it’s the best idea.”

“I just don’t see how getting charged four times as much for a paan gives anyone a good first impression of India,” Rohit said, his voice low. “But I know I’m new, and I need to learn to do it right.”

The man extended his hand. Rohit took it.

His name was Mr. Salim, and he was originally from Hyderabad.

“Hyderabad . . . India?” Rohit asked.

Mr. Salim laughed, but there was kindness in his eyes.

“But . . . you’re Indi—I mean . . .” Rohit stammered, blushing.

Mr. Salim waved his hand to cut Rohit off. “Yes, I’m Indian. And I choose to work here. I consider it an honor, in fact.”

“I haven’t seen you around,” Rohit said.

“Oh, I don’t work in New Delhi sector,” Salim replied.

“I don’t either,” Rohit said, “I work in Old Delhi.”

The man laughed again. “Where you work is not Old Delhi,” he said.

When Salim invited Rohit home for dinner, Rohit was thrilled, excited to eat somewhere other than the quick-serve canteen on the ground level of his company dormitory.

Mr. Salim’s apartment was in a predominately Muslim residential colony, a quick ride from the India World complex via Delhi Hyperloop. Still, when Rohit took his first step into his new friend’s home, he was transported thousands of miles away. The smells—coriander, ginger, turmeric, whole wheat roti cooking on a cast-iron pan—were everywhere in India. But the particular mix in Mr. Salim’s apartment took Rohit to weekends spent at his grandparents’ home, sitting at the kitchen island impatiently waiting for dinner to be ready.

“That smells incredible,” Rohit said. He pulled at the neck of his sweater, suddenly aware he hadn’t brought anything to his first dinner invitation in the country. “Ahh—I should have brought some wine, or—”

Rohit’s company-issued phone shrieked like a smoke alarm. He dug into his pocket to silence it, blushing and sheepishly apologizing to his host.

“It has lost signal,” Mr. Salim explained, pointing around the room, “Faraday cage. Sometimes it’s nice to be able to speak in private, don’t you think?”

Mrs. Salim emerged from the kitchen to greet them. “Rohit, you’re one of the new ones, eh? Welcome to our home, I’m happy you could join.”

“Relatively new, yeah. Thanks. Thanks so much! You have a beautiful home,” Rohit said, pawing at the back of his neck. He wondered if he should touch her feet as his parents had always taught him to touch his grandparents’ feet in respect when greeting them. But was that only for elders? He settled on pressing his hands together in namaste and giving her a quick nod. She smiled and returned the greeting before turning to her husband. “Suno, daal par nazar rakh sakate ho?”

“Yes, of course,” Mr. Salim replied. “Come,” he said to Rohit, “we’re needed in the kitchen.”

Rohit stirred two bubbling pots of curry and daal. Beside him, Salim flipped rotis and laid pakoras onto an infrared cook surface that flashed pakora-shaped light onto the fritters, cooking and crisping them in alternating bursts of long- and short-wavelength light. Mrs. Salim reappeared twenty minutes later in a new outfit and set the table. Once Mr. Salim and Rohit brought the food to the table, the three sat to eat.

“I didn’t understand something you said today,” Rohit said.

“Oh?” Mr. Salim said.

“That I don’t work in Old Delhi. I work in Chandni Chowk—isn’t that Old Delhi?” Rohit asked.

“Ahhh, no,” Mr. Salim said, pushing his glasses up his nose.

His wife chuckled. “Now you’ve got him started,” she said with a smirk.

“The Mahabharata is the greatest and the longest epic ever written. It is Indian,” Mr. Salim said, with a note of reverence. “The Vedas—tomes of ancient, timeless knowledge—are millennia old. From those Vedas, more than five thousand years ago, India gave us yoga,” he said, drawing out the last word. He looked up to the ceiling before he continued, “hundreds of years before Christ was even born, Prince Siddhartha sat beneath the Bodhi tree, attained enlightenment, and gave the world the teachings of Buddhism. Hinduism. Jainism, trigonometry, the Fibonacci sequence, chess. What do all these have in common, Rohit?”

“They were Indian,” Rohit said.

“They were old India,” Salim corrected. “In the late nineteen hundreds, long after partition and freedom from British rule, India exploded. It grew but lacked discipline and vision. In the early two thousands, it became clear to many that clinging to the old ways was holding us back. India was one of the twin tigers of Asia, but she was ceding her power to China. Do you know what changed?”

Rohit struggled to recall his Indian history, “Modi’s monetary reform? The clean air revolution of twenty twenty-eight? Jio’s AI platform getting adopted worldwide?” he offered.

Salim shook his head. “India World.”

“Wha—but India World is a theme park,” Rohit argued, “for foreigners.”

“When India World started, it was an offshoot of the National Museum of India in Delhi, and its charter was to educate not just the world, but India herself. Its programs spanned the country. They ignited something buried deep, almost forgotten. And that, my friend, is what saved India, what brought her back from the brink.”

“A museum?”

“An education in what we had brought to this world, and who we could be,” Mr. Salim said quietly.

The three sat in silence until Mrs. Salim spoke. “He’s right. It’s not well known outside, but inside India, India World is credited with re-instilling India’s pride. Our country had spent decades copying Western culture—its movie plots, its business models, its apps, fashions, and morals—in the process, we lost ourselves. India World reminded us of who we were.” She paused to sip from her glass. “You know, to this day, New India party leadership requires elected officials to go through India World training before taking office. Ji led that effort. Still does,” she said, nodding at her husband.

“You did?” Rohit asked Mr. Salim incredulously, “I didn’t think you were that old . . .”

Mr. Salim winked. “We also invented plastic surgery, Rohit.”

The next day Salim found Rohit as he donned his uniform before his shift. “Rohit, do you not celebrate Raksha Bandhan?”

Rohit’s left hand clasped his bare right wrist. “I do . . . but I’m an only child.”

Salim dug into his pocket, removed a simple bracelet made of red and orange intertwined threads, and draped it over Rohit’s wrist.

Rohit furrowed his brow. “But you’re Muslim,” he said. “Do you celebrate?”

“No, of course not. But these things matter here, even more than where you’re from. Use it to your advantage,” he said, tying the string around Rohit’s wrist.

When Rohit stepped out of the locker room and into the park that morning, he wasn’t working for a paycheck anymore, nor in hopes of winning residency. His role in India’s future had begun to feel a little more meaningful—and his automated assessments picked up on the change. His ratings became near-perfect by the end of the following month. This allowed him to rotate through new areas of the park of his choosing, and he often spent the end of his days assisting Mr. Salim with small tasks. Still, Rohit knew he’d never advance to park management—his foreigner status was a publicly accepted form of low caste.

Over the months that followed, Rohit became a fixture at the Salims’ dinner table, and he and Mr. Salim grew closer. One day, he asked the older man why he’d never taken on a role in management, still choosing to work directly on the park grounds, despite his seniority. Salim’s brow creased, and the man muttered something about his “dark skin” and “invisible quotas.” Rohit didn’t entirely understand, but he took this to mean his mentor was stuck just as he was. Though it had once inspired India’s progressive turnaround, Rohit was discovering that India World’s role today was less about pulling its people into the future and more about sharing a selective story of India’s past with its many foreign visitors.

Rohit waited impatiently as the phone rang on the other side of the world. He had rarely spoken to his parents since he’d left the States—the time difference and his shame for failing at his job had initially kept him away—but now he couldn’t wait to see them.

His mother answered, holding her phone rigidly in front of her and peering down at it through her bifocals. In the background, Rohit could hear the banter of commentators narrating a football game.

“Hiii,” he said in a singsong voice, his mouth breaking out in a wide smile.

“Hello, beta!” his mother sang back, her cheeks betraying the grin she was attempting to conceal.

“Missed me, Mum?” Rohit asked.

She rolled her eyes. In the background, Rohit heard a crowd erupt in cheers.

His mother leaned forward, swinging the phone away, and sneezed into a handkerchief. When she returned to the screen, he searched her eyes instinctively, but they were clear and bright. She looked . . . healthy.

“You look good, Mum,” Rohit noted. “Have you been using the new micronasal filters I sent you?”

“Nahin, nahin,” she said, waving her fingers in front of the camera as if to sweep his comments aside. “It’s Papa’s doing,” she said.

“Did he finally replace the air filters like I’ve been telling him? I saw there were wildfires again.”

She laughed, and he noticed her shoulders weren’t slumping like they usually did. She actually looked taller, stronger. “He got his motion passed.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Oh ho! The tower carbon reclaimers, beta. He’s been pushing the city council for a year. You know how he is when he feels something is right . . . he won’t back down. Always working on some project.” She drew a long breath and glanced off-screen at his father, a look of pride on her face. “They installed them on every other street last month.”

Rohit’s stomach tightened. He hadn’t known about his father’s campaign. Had his father told him and he hadn’t paid attention? All this time, he’d been pushing his parents to save their own lungs, and his father had cleaned the whole city’s air instead. Why hadn’t he thought to help everyone?

His mind suddenly returned to the second time he’d seen the man who had once followed his family through the parking lot of that taqueria years ago. He’d been wearing the same faded Giants cap and red-and-black hunting coat as before. Only this time, he was sober, and he was standing at their front door.

His face was scruffy, he smelled of smoke, and he seemed uncertain on his feet, but when Rohit’s dad saw him, he greeted him warmly with only a hint of imitation cowboy in his voice. It turned out his father had given the man his card that first night. He’d kept talking to him, had helped him out, and somehow had convinced the man to join them for Thanksgiving dinner a year later. The two watched football together, loudly hooting for the 49ers. The man had hugged Rohit’s father on the way out that night.

“Beta, it’s fine, don’t worry,” his mother said.

Rohit sighed. “Okay. Well, it’s nice to see you looking so healthy and happy. It makes it easier to be so far away.” He stopped when his mother’s face fell. “What’s wrong?”

“Nothing.”

“Mum . . .”

“Suno!” she yelled to his father, then placed her phone down on the table, giving Rohit a view of the ceiling. A few moments later, both of his parents appeared on the screen, his dad wearing a wide grin and an enormous winter jacket, his mother looking away, sullen.

“Rohit, they’re winning fourteen zero,” his father exclaimed. The man had spent decades taking his son to 49ers games, but he never took an interest, or even understand the rules. Rohit had secretly streamed cricket matches to his AR specs while sitting in the hot bleachers beside his dad. Now Rohit just shrugged.

“Cool, Papa. What’s with the jacket?”

“Oh, I was shoveling Dr. Suda’s walkway. He’s too old to do it himself.”

“Should you be shoveling, Papa?”

“It’s just a few inches,” he said quickly. “We’re retired. What else can we do with all our time?”

“Why is Mum sad?” he asked, changing the subject.

“We don’t need an air filter, beta. Your mother doesn’t have her coughs anymore. She’s fine.”

“Papa . . .”

The old man glanced at his wife. When his eyes returned to his son, his grin had slipped away. “Rohit . . . we haven’t heard from you in a long time.” He shook his head slowly. “And I think Mummy thought . . . maybe you were calling to say you were coming back.”

Rohit swallowed hard. “Sorry,” he whispered.

“Beta, what is that on your wrist?” his mother asked, breaking the silence.

Rohit turned his wrist and glanced at the red and orange threads Salim had tied there. “A rakhi,” he said.

“You have no sister, Rohit. Who could have sent you a rakhi?”

“It’s just . . .” Rohit said, “Sal—a friend gave me this one. He said it would help me at work.”

His mother cast a sidelong glance at his father before turning back to the screen. “Why would a rakhi help you at work, Rohit?”

Rohit squirmed. “I dunno, I guess it just makes them see me as . . . one of them.”

His mother frowned.

“We are so glad you called. Tell us everything we’ve missed!” his father said.

Rohit told them of his months in India. Of the technical marvels he’d seen, like the individually customized, nutritionally dense meals that magically arrived moments before he felt the first pangs of hunger, delivered by India’s automated tiffin network, and the audio guide that not only translated the languages of all of India World’s guests directly into his ears but also suggested gestures and references to make them feel more welcome. He left out the stiff reprimand from his boss a month into his new job, but told them how he’d steadily improved at his work, and even made friends. He alluded to Salim but didn’t go into detail, not wanting his parents to feel they’d been replaced. Throughout, he carefully checked his enthusiasm, to keep from letting his love of his new country shine through too strongly.

When he finished, Rohit’s father cleared his throat. “You know, your grandfather would often speak of India the way you do.”

“Really?” Rohit asked, his voice rising.

“All the time. He sometimes regretted not moving back. When we were little, he and your grandmother would talk about returning once your uncle and I were grown.”

“Why didn’t they go?” Rohit asked.

“When they were young, and just starting out here, they still saw India as their country. America is the Land of Opportunity, of course. They learned things they never could have learned elsewhere, earned more in a year than they would have in a decade if they’d stayed. America gave them everything. But they wanted to take all that to their country. Your grandmother would tell me about India’s past and say that India needed all her children to help it blossom again. All these things you’re learning in India, all of what you’re gaining—”

“Of course, that makes so much sense,” Rohit said. “So why didn’t they go back?”

Rohit’s father sighed. “By the time your uncle and I were grown, it was too late for them. India no longer felt like home.”

“Beta, don’t let them change you,” his mother interrupted suddenly.

“What do you mean, Mum?” Rohit asked.

“You’ve always loved India, and of course, we are happy for you. You should love it. But you are more than just Indian, more than just Hindu. Do not forget where you came from. You be you.” She turned away, wiping her cheeks. Rohit cringed, and his father’s eyes stayed on him, squinting.

An alert summoned Rohit to report to Mr. Mittal immediately. Six months had passed since his initial rebuke, but the memory of that visit left his fingers and toes frigid, his stomach churning as he walked through his boss’s door.

“Rohit! So glad to see you, beta,” Mr. Mittal exclaimed, sliding around his desk and trotting to Rohit, hand extended.

Rohit took Mr. Mittal’s hand and felt some, but not all, of the tension leave his body.

“Sit, sit,” Mr. Mittal said, waving at the sofa in front of his sleek glass desk. As Rohit took a seat, his boss leaned back against the tabletop and crossed his arms, looking at Rohit and nodding. “You’ve had quite a few months here—I’ve been watching you,” he said, pointing at his eyes with the index and middle fingers of his right hand. “I see everything,” he reminded Rohit, then laughed. “I was worried about you, but you’ve come far. Very far. You’ve really blossomed here, Rohit. Do you feel that way as well?”

Rohit straightened his posture. “Yes sir, of course. I do.”

“Good, good,” Mr. Mittal said, nodding quickly. “Well, I’ll get right to it. I like what I’ve seen, and I’m promoting you.”

Rohit’s tension fell, and he broke into a goofy grin.

“Splendid! I thought you’d be pleased. We’ll have your two-year work visa extended. You’ll start earning credits toward a permanent alien classification immediately. I’ve seen you spend a lot of time with Mr. Salim, and I’m having you take over from him. He’s been there too long, and fresh blood will do his department some good. Five years from now, you’ll be able to file an application for a permanent alien card and work anywhere in the country. Of course, I hope you’ll stay with us.” Mr. Mittal grinned in a way that implied it was less hope and more of a requirement, but Rohit barely heard a word.

All of a sudden, Rohit discovered that he was on his feet, his head pounding, and Mr. Mittal was staring at him in surprise.

“What did you say?” Mr. Mittal asked, confused.

Rohit blinked rapidly. What had he said? “I can’t do it. I can’t stay,” he repeated, shocked at his own words.

“Beta,” Mr. Mittal began, his face twisting between compassion and anger, “I don’t need to tell you this is an opportunity very few get. I hope you understand how rare this is.”

Rohit’s fists felt cold and clammy. Salim’s speech about the value of India World and his grandmother’s words about India needing her children echoed in his mind. “Sir, I’ve learned so much here, and I’m grateful. I see now the value of India World, and how much my country needs a place like this.”

Mr. Mittal chuckled. “Who would want to visit Old America, Rohit?”

“Plenty of people,” Rohit sputtered, heat rising to his face.

“America is in ruins. A corrupt shell of hatred and entitlement run by hucksters.”

“We invented electricity, the automobile, the smartphone, football—” Rohit began.

“At least Europe has its cathedrals and palaces. Who will want to see the ruins of a fallen British colony’s one-story prefabricated strip malls? Temporary architecture for a temporary society,” Mr. Mittal growled.

“We were a country that welcomed outsiders with open arms,” Rohit insisted, “and took care of our neighbors, spread democracy, stood for liberty—”

“A mere blip in history. Surely you don’t think American culture has any significance today, Rohit?”

“No . . .” Rohit hesitated, glancing at the photographs affixed to Mr. Mittal’s walls: the Taj Mahal, the free Kashmir liberation announcement, the grand Mughal palaces of Delhi’s past. But no photos of the bloodshed caused by decades of skirmishes with Pakistan, nor the hardships forced upon generations of low-caste Dalits, nor the millions of female fetuses secretly aborted in preference for male offspring.

“Didn’t India, too, need help to find itself once?” Rohit asked.

Mr. Mittal scoffed. “I quite doubt America’s past, or future, has anything in common with ours, Rohit.”

But Rohit knew he was wrong. America had just as many skeletons in her own closet. India’s pride may have returned, but India World hadn’t fixed India.

Rohit took a deep breath of clean air and swung open his parents’ front door. A familiar but unknown aroma greeted him. Onions, cumin, garam masala, and . . . ketchup?

“I’m home!” he cried out.

His father emerged from the kitchen in a stained apron, spatula in hand. “Welcome back, beta! How was your flight?”

“Long,” Rohit said as they embraced. “What’s that smell?”

“Your father’s been planning it since we heard you were coming back,” his mother said, appearing with a silver tray.

“New recipe, beta,” his father said, his chest puffed out and his spatula raised. “Masala burger. Best of both worlds!”

His mother walked to her son, dipping two fingers in a dish of water, then in the vermillion powder on her tray. Rohit leaned forward, and she dotted his forehead with color, pressed a pinch of rice to the mark, then transferred some M&M’s from her tray to his mouth.

“Thanks, Mum,” Rohit said, blinking rapidly as he straightened up.

Turning back to his father, he asked, “Papa, I was wondering . . . You need a hand with any new projects?”

“Absolutely, beta. Come, come,” his father said, putting an arm around his son’s shoulders. “There is much to do.”

“India World” copyright © 2022 by Amit Gupta

Art copyright © 2022 by Jasjyot Singh Hans

I thought some translations might be useful:

Rohit’s mother says, “dekho kesi baat kar ra—” That’s “Look what kind of thing–” and the verb phrase cuts off. I assume it would finish with “kar raha hai” to mean “he is doing.” It could also mean “Look what kind of thing he is saying.”

Mrs. Salim says, “Suno, daal par nazar rakh sakate ho?” and that is “Pardon, could you keep an eye on the lentils?”

@1: Thank you, the translations and explanations are very much appreciated!

I liked the theme and the story gave me food for thought regarding the sometimes conflicting loyalties and aspirations of members of diasporas. The background of shifting geopolitical power spiced things up in an interesting way.

While I enjoyed the fluid writing, I didn’t feel like the story was flowing in a very natural way. In particular, the resolution felt like the cathartic release of a built-up tension but without that accumulated frustration to justify it. It came a bit out of nowhere.

I was surprised and filled with many different and difficult thoughts and emotions, which is a good thing.

At first it seemed to be only doing a marvelous job of tinting history, which was making me sad and angry. Still the writing was great so I kept reading. Then finally it reflects some of the realities of modern India, although barely touching some of the very real atrocities, many which are still happening today. I only wish there had been more of the story after the turning point.

Got me excited at first with its title (on this site), but unfortunately turned out to be formulaic and ultimately shallow. It’s a short story, granted, but still, the writer could’ve done so much more than mention just the usual suspects in his alt-history…